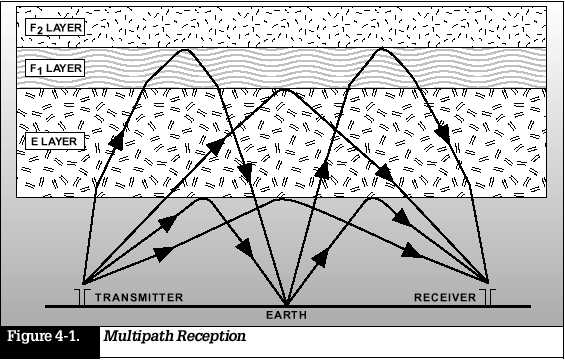

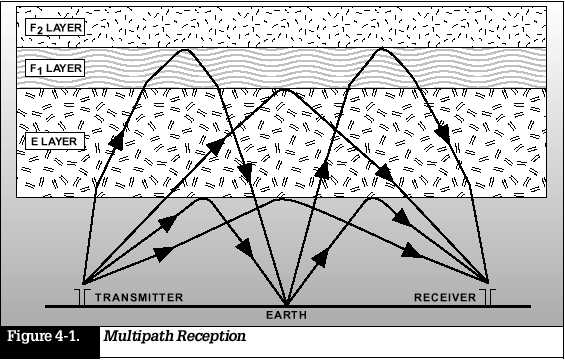

Signals from a transmitter reach the receiver via multiple paths (Figure 4-1). This causes fading, a variation in average signal level because these signals may add or subtract from each other in a random way.

While listening

to the radio during a thunderstorm, you’re sure to have noticed interruptions

or static at one time or another. Perhaps you heard the voice of a pilot

rattling off data to a control tower when you were listening to your favorite

FM station. This is an example of interference that is affecting a receiver’s

performance. Annoying as this may be while you’re trying to listen to music,

noise and interference can be hazardous

in the world

of HF communications, where a mission’s success or failure depends on hearing

and understanding the transmitted message. Receiver noise and interference

come from both external and internal sources. External noise levels greatly

exceed internal receiver noise over much of the HF band. Signal quality

is indi-cated by signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), measured in decibels (dB).

The higher the SNR, the better the signal quality. Interference may be

inadvertent, as in the case of the pilot’s call to the tower. Or, it may

be a deliberate attempt on the part of an adversary to disrupt an operator’s

ability to communicate. Engineers use various techniques to combat noise

and inter-ference, including: (1) boosting the effective radiated power,

(2) providing a means for optimizing operating frequency, (3) choosing

a suitable modulation scheme, (4) selecting the appropriate antenna system,

and (5) designing receivers that

reject interfering

signals. Let’s look at some of the more common causes of noise and interference.

Natural Sources of Noise

Lightning

is the main atmospheric (natural) source of noise. Atmospheric noise is

highest during the summer and greatest at night, especially in the l- to

5-MHz range. Average values of atmospheric noise, as functions of time

of day and season, have been determined for locations around the world,

and are used in predicting HF radio system performance. Another natural

noise source is galactic or cosmic noise, generated in space. It is

uniformly

distributed over the HF spectrum, but does not affect performance below

20 MHz.

Man-Made Noise

Power lines, computer equipment, and industrial and office machinery produce man-made noise, which can reach a receiver through radiation or by conduction through power cables. This type of man-made noise is called electromagnetic interference (EMI) and it is highest in urban areas. Grounding and shielding of the radio equipment and filtering of AC power input lines are techniques used by engineers to suppress EMI.

Unintentional Interference

At any given time, thousands of HF transmitters compete for space on the radio spectrum in a relatively narrow range of frequencies, causing interference with one another. Interference is most severe at night in the lower bands at frequencies close to the MUF. The HF radio spectrum is especially congested in Europe due to the density of the population. A major source of unintentional interference is the collocation of transmitters, receivers, and antennas. It’s a problem on ships, for instance, where space limitations dictate that several radio systems be located together. For more than 30 years, Harris RF Communications has designed and implemented high-quality integrated shipboard communications systems that eliminate problems caused by collocation. Ways to reduce collocation inter-ference include carefully orienting antennas, using receivers that won’t overload on strong, undesired signals, and using transmit-ters that are designed to minimize intermodulation.

Intentional Interference

Deliberate

interference, or jamming, results from transmitting on operating frequencies

with the intent to disrupt communica-tions. Jamming can be directed at

a single channel or be wide-band. It may be continuous (constant transmitting)

or look-through (transmitting only when the signal to be jammed is present).

Modern military radio systems use spread-spectrum

techniques

to overcome jamming and reduce the probability of detection or interception.

Spread-spectrum techniques are tech-niques in which the modulated information

is transmitted in a bandwidth considerably greater than the frequency content

of the original information. We’ll look at these techniques in Chapter

7.

Signals from

a transmitter reach the receiver via multiple paths (Figure 4-1). This

causes fading, a variation in average signal level because these signals

may add or subtract from each other in a random way.

SUMMARY

• Natural (atmospheric) and man-made sources cause noise and interference. Lightning strikes are the primary cause of atmo-spheric noise; power lines, computer terminals, and industrial machinery are the primary cause of man-made noise.

• Congestion of HF transmitters competing for limited radio spectrum in a relatively narrow range of frequencies causes interference. It is generally worse at night in lower frequency bands.

• Collocated transmitters interfere with each other, as well as with nearby receivers.

• Jamming, or deliberate interference, results from transmitting on operating frequencies with the intent to disrupt communi-cations.

• Multipath

interference causes signal fading.